The 'Over and Under' Philosophy

A principles based approach to investing

I started writing Overlooked and Undervalued in 2023, and since then, my portfolio has seen many changes.

But what hasn’t changed are my five investment principles. These remain constant and are re-stated every year in the Annual Update. Taken together, these principles provide a guiding philosophy and unite my actions along a deliberate and consistent path.

I’m sharing these with you. Primarily, to help readers (and potential readers) better understand the type of investments covered by Overlooked and Undervalued. But also, to provide some wider context on my results and portfolio management.

I hope you take away as much from reading this, as I have benefited from writing it.

Thank you as always for following along.

Run towards the overlooked, the odd, the illiquid, the small, and the unpopular.

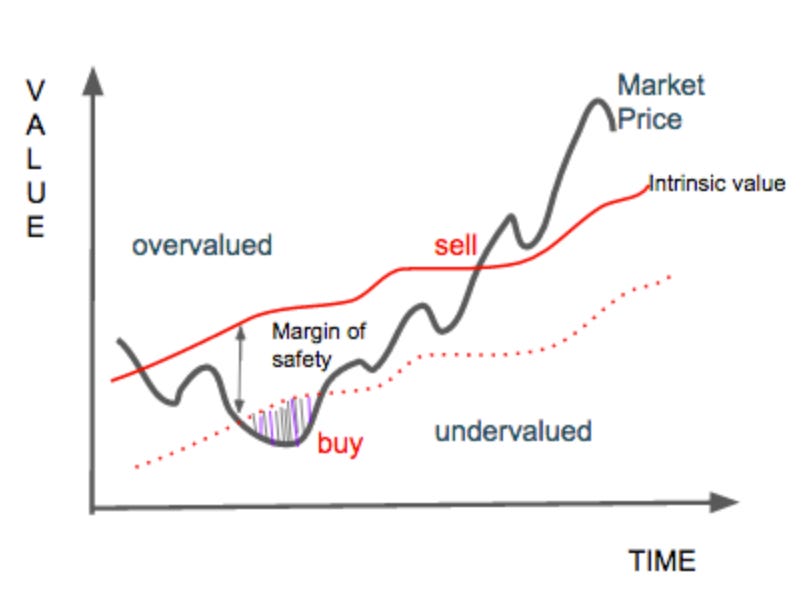

As an active investor, I’m looking for securities where price has diverged from value. All else being equal, the lower the price, when compared to (intrinsic) value, the greater the opportunity.

This diagram demonstrates the point. I want to buy when a security is undervalued and sell when it becomes overvalued.

But, what causes this undervaluation? And, where are these opportunities found?

To answer these questions, we’re looking for areas of the market when undervaluation is (a) the largest, and (b) the most abundant. Two factors that would increase our probability of earning excess returns.

Over time, I’ve become increasingly convinced that popularity is the most important cause of miss-pricing.

The more popular a company becomes, the more investors want to own it. Therefore, the more likely it is that the price is ‘bid up’ to a level that sits at, or above, its true value.

I also believe the opposite is true. When a security is unpopular, there are less people that want to own it, and so the price is more likely to languish well-below its true value.

Seth Klarman, a US investor with an enviable track record, seems to agree. He is attributed to a wonderful quote stating that generally the greater the stigma of revulsion, the better the bargain. Anthony Bolton, one of Britains most successful investors, inverted the idea and has compared popularity to risk.

Roger Ibbotson, of the Yale School of Management, even published a short book on the subject.

Popularity: A Bridge between Classical and Behavioural Finance provides quantitive evidence that unpopular securities can lead to outsized returns (for those who are interested, it’s available to download here).

This mindset brings other benefits.

Firstly, it’s possible to find unpopularity in all environments. Even as a bull market drives higher, there are still those companies that don’t fit in with the current hype.

Secondly, unpopularity doesn’t rely on a particular style box (for example large cap quality or growth). This means it’s less likely to suffer when a popular style (or most recent fad) inevitably stops working.

As a principle, I focus on unpopularity. But I added the overlooked, the odd, the illiquid, and the small, which are variations on the same theme. Unpopular areas of the market, where I expect undervaluation to be large and opportunities most abundant.

Counter cyclical. A buyer in times of financial panic, otherwise patient.

It’s common knowledge that holding cash for long periods is a terrible idea. At best, cash earns investment returns similar to inflation, and at worst, purchasing power is rapidly eroded.

Even with this knowledge, I often hold cash (or equivalents).

This is because market crashes are scary, even for professional investors. Nobody buys securities in the good times thinking that they will sell out in a financial panic, at the worst possible time.

However there are countless examples of people who do. Because it’s painful watching your family’s wealth diminish. And selling reduces this pain.

Over time, I’ve found the best way to fight this urge is to hold some cash.

Firstly, this approach gives you the flexibility to buy, at the best possible time, when assets are deeply discounted. But more importantly, it helps maintain a positive mindset when all other external factors are negative. Financial panics bring negative news, poor results, and bucket loads of fear.

Holding some cash allows me to think counter cyclically. Instead of running for the hills, I’m searching for good assets being thrown away by fearful investors.

For most professionals, adopting this approach is a marketer’s worst nightmare. Very few clients would be willing to pay fees for holding cash. Even fewer, would be happy with the drag on results during rising markets.

The flip side to this, is better results during the most difficult periods. At a time when everyone else is doing poorly.

To me, this tradeoff makes perfect sense.

Ultimately, I’m not trying to beat the market, especially over shorter periods. Instead, I’d describe myself as an absolute return investor, who aims for an adequate returns, irrespective of the investing environment.

Performance in any single year is unimportant - compounding takes time.

I’ve observed a common trait amongst professional investors. Supposedly long-term investors spend most of their time writing about short term results.

Investment letters are released quarterly and most cover quarterly changes in the portfolio. Alongside this, updated performance figures are used either to advertise strong performance or justifying poor performance.

To me, this is at odds with the goal of achieving long-term results. Surely, if you think about an investment with a five year time horizon, and your investment thesis remains intact, a single quarter, or even a single year makes very little difference.

As Nassim Nicolas Taleb succinctly stated - when an investor focuses on short-term investments, he or she is observing the variability of the portfolio, not the returns – in short, being fooled by randomness.

In today’s investment landscape, I think there are too many investors and clients being fooled by randomness rather than building a truly long-term mindset.

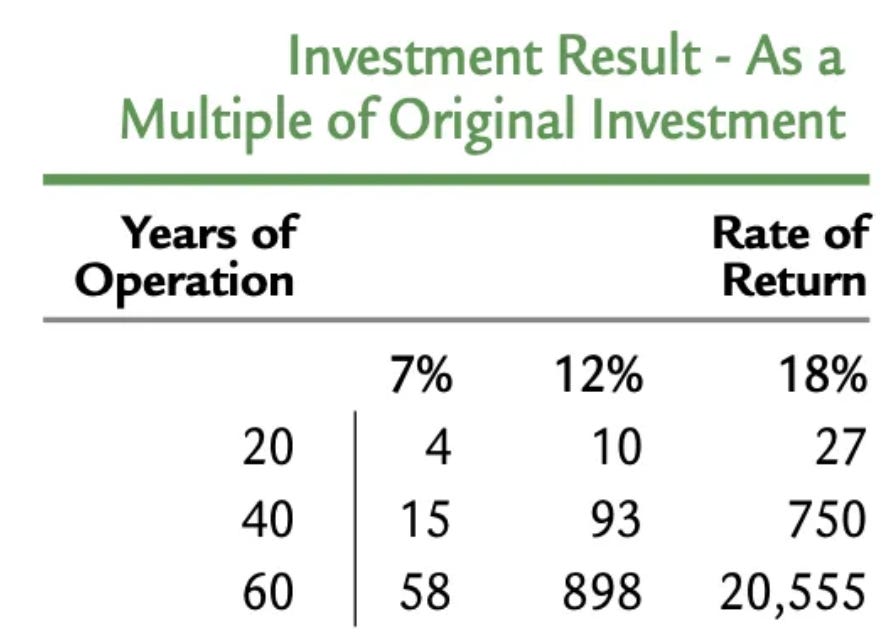

Instead, I want to benefit from the power of compound interest. Where wealth creation grows almost exponentially, provided that adequate returns can be maintained for very long periods.

The chart below, which I’ve borrowed from Guy Spier’s 2015 investor letter, demonstrates the power of compound interest. As you can clearly see, the longer the time frame, the better compounding actually works.

Given this context, I remain unconvinced that myopically focusing on a single quarter, or even a single year, makes any sense for the long-term investor.

Survival trumps being/looking smart.

It’s a statistical reality that in most years, stock markets go up.

Therefore, in most years, it’s possible to add leverage to an investment strategy and achieve above-average results.

This leverage could be introduced at the portfolio level or by betting on the equity of highly indebted companies. Either would amplify volatility, creating a strategy that earns better results in rising markets.

However, the price you pay, is larger drawdowns in falling ones.

Being able to endue this portfolio volatility is critical for long-term investment success. When leverage amplifies losses, it limits an investors ability to survive.

Large losses are extremely difficult to handle, both practically and emotionally. As the loss grows, it becomes exponentially more difficult to recover back to breakeven. As the below chart demonstrates.

Whilst on the surface, these dangers may appear simple and obvious, human emotion (fear and greed) can cause investors to compromise prudent risk management in an attempt to maximize returns. Especially during the good times.

I think the best writing on this subject comes from Chapter 17 of The most important thing by Howard Marks. Where he discusses the difficult choice all investors must face. Either to maximize returns through aggressive tactics, or build in protection through margin for error.

He goes onto write that the amount of safety you build into your portfolio should be based on how much potential return you’re willing to forgo. There’s no right answer, just trade-offs.

In these few sentences, Marks distinguishes between optimising, which means you try to set up your affairs so that you’ll be able to last for the long term. And maximising, which means you just trying to get the most you can, as soon as you can.

Given this choice, I try to optimise.

To be less concerned with posting knock-out performance when everyone else is doing well. A result that could easily be achieved by increasing leverage.

Instead, I aim to participate reasonably in a rising market, without giving too much back in a falling one. Ideally, out-performing over a full economic cycle.

Throughout history, there are countless examples of investors losing their life savings investing in the latest fad, or making an over-leveraged bet on a popular idea. I’m certain that every single one of those investors thought they’d be smart enough to sell out before the party ended.

I don’t think I’m that smart. So I stay away from leverage and I don’t invest in highly indebted companies. To me, survival trumps being/looking smart!

Simplicity. Everything else on the too hard pile.

Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face, is one of Mike Tyson’s most famous quotes. However it is not the full quote - it continues then, like a rat, they stop in fear and freeze.

Anyone who studies financial history will know that being punched in the face has been a regular occurrence for market participants. Roughly every decade, a large drawdown spooks investors. And, whether we stop in fear and freeze, or we’re able to act logically, can define our investment career.

I feel stress, like anyone else. So during a market drawdown, my anxiety builds. Sometimes reaching a level where completing complex tasks, or understanding complex problems becomes increasingly difficult.

We can study history, we can mentally prepare, and we can make plans. However, the best laid plans often go awry because the ultimate reality differs from our preconceptions.

To combat this, I’ve found the best way to maintain a structured and logical thought process is to focus on simplicity at all levels.

In every part of my process, I’m trying to cut through complexity and focus on what is essential. A goal that has drawn me towards investing in simple businesses with simple balance sheets, using simple thesis. No matter the market conditions.

At the most difficult times, I want to be able to quickly and easily compare what I own to my wider opportunity set. A vital task, which becomes almost impossible when investment cases are complex.

Monish Pabrai sums up this point in The Dhandho Investor. Buy painfully simple businesses with painfully simple theses for why you’re likely to make a great deal of money and unlikely to lose much.

For everything else, there's plenty of room on the too hard pile!

Disclaimer. This article is for informational purposes only, and should not be seen as investment advice. Please do your own research before investing in any company mentioned.

What a brilliantly pragmatic, honest, insightful thought provoking, ego free post.

Thank you